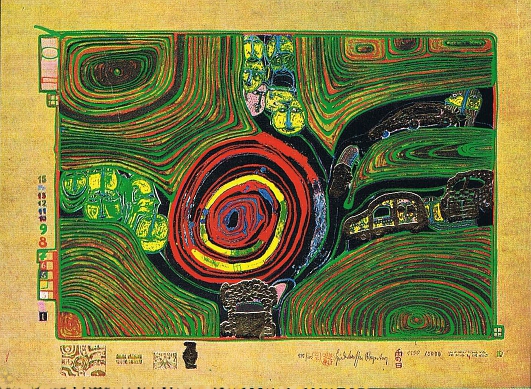

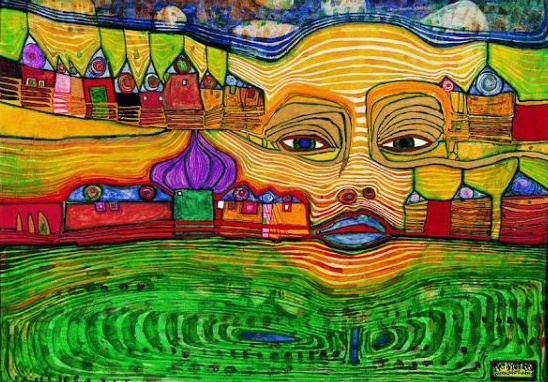

Friedensreich Hundertwasse

Rap for Toni Wolff's Schema

in shifting one in four and three with one

in harmony hear shaping

relational forming

exciting the imagination

scatting, shifting

movement inviting space

dissolving barriers in body in soul

identities begetting longing

centering provoking

an imagining deity cracking open history moving within

earth mother sky father

together as origin

touch origin seething

possibility containing field containing

hearth mama, papa

leaders warriors

soothsayers shamans

containing fields of desire night spirits embracing

complexity swift horse

power from the sea of possibility

from the void moving

emerging desire begat sea begat land begat stars

Pablo Picasso, Woman in White

By joining in the work of the Chilean School of Ecofeminist Spirituality and Ethics in 2001, I became conscious of a trans-American source of psychological energy for women birthing an inclusive spirituality. South American founding women sought out a spirituality nurtured in community, one expressive of the dignity of women's work and status, one affirming youthful innovation: the energy in the songs of musicians and delegates gathered at the United Nations.

Before traveling to the Chilean School, I knew few sources of ecofeminist thought despite a widespread interest in earth spirituality among both women and men. An exception was Vandana Shiva's focus on ethical questions relating to ecological and feminist perspectives. In confronting political power structures, Shiva uses a symbol capturing the ethical question of sustainability: the seed. Her analytic clarity, focused on actions to make water and food dynamic national conservation policies, names the immediate threats to our planet's material resources being exploited in service to capitalistic wealth and first world interests. Hers was the focus I carried to Santiago when I first met with the theologians and community organizers gathered there. I looked forward to the theological work of the School's teachers.

When I was three years old my parents, Earl and Margaret, gave me an initiatory gift: My Book House, a collection of twelve books. The literature from the world beyond Ironwood, Michigan seduced me and I learned to read. I read tales of great forests, of goblins, of Norse sea adventures revealing why the sea is salt. Since childhood I have known where to turn if I should need to discover the world: I turn to stories of creation.

So it was that I began preparatory studies after being invited to participate in the South American School of Ecofeminist Spirituality and Ethics. I began with Jean Gebser's analysis of the evolution of human consciousness, his Ever-Present Origin. I recognized that Gebser's analysis of aperspectival awareness would relate to the School's approach to the history of spirituality. I reviewed the idea of hybridization and sought out so-called hybrid artists who speak to bicultural identities.

I began with questions: as community organizers seeking a spirituality feeding their concern for justice for the marginalized, would these ecofeminist theologians find the Mother Earth to be the relational archetype? Had they already gravitated toward the images in indigenous stories, toward goddesses of the descent to lower regions, toward Biblical figures, toward the Sin Eater Goddesses, toward stories of the mysteries of spirits who sit at the crossroads? The Chilean School was directed by women familiar with ritual, with myth, with imagery. Among these women seeking a spiritual life to sustain their work as community organizers, Ana Mendieta's performance art evoked response. Mendieta captures women's cultural vulnerability in experiencing affinity with the natural world.

Ana Mendieta, Untitled from Silueta Series

Since Toni Wolff 's schema of relational forms could be understood as supporting a maleocentric myth in which women are defined by their relationships to men, I chose between disproving her schema and probing its potential to express social conditions created by colonial perspectives being challenged by postcolonial insights. While Nor Hall and Madonna Kohlbenschlag and others used Wolff's relational forms to evidence feminine creative energy, I wondered if Wolff's Western European perspective could serve to portray colonial structures and allow an analysis of social misrecognitions and present internalized oppressions. Wolff's initial presentation in 1934 pointed out the critical symbolic significance of excluding feminine divine figures from Christian iconography.

Would the women coming to the School identify with Wolff's relational forms as diverse expressions of relational orientation? Would we find an authentic spirituality in the archetypal Earth Mother containing all possibilities? Would the women critique the lack of feminine divine images in their own cultures and in the disregard for indigenous imagery and would they find images of power in early cultural perceptions? Would some among them point out the lack of attention to contemporary queer theory and the assumed ascendancy of heterosexual pairings? Knowing their familiarity with both Paulo Freire's pedagogical methods and with hermeneutics, I anticipated how much I had to learn from these South Americans. I reviewed Mary Douglas' Purity and Danger and Rosemary Radford Ruether's Goddesses and the Divine Feminine.

Liliana Kleiner, Swimming Home

When I sought out Asian and African cultural perspectives, I found indications that nomadic peoples carry on traditions which parallel the functioning of three of Wolff's four forms: the indispensable hearthmakers (the Mother form), the horseback riders trained in military skills (the Amazon form), the priestesses whose rituals guide decision making (the Medium form). It is in the new materialisms, in nomadic theory, and in the French philosopher-analysts, Deleuze and Guattari, that I found inspiration for my intuitive suspicion that the social role of the fourth form, the hetaira, is the creation of colonial cultures in which the hetaira emerges as an occupation and a socially distinct formulation within communities in which some males (property owners) held the rights of citizenship. Social evolutions which produced the ideal of a democratic citizenry did not assure equality for women nor eradicate conditions which created poverty and scarcity. Instead such societies created roles for slaves, concubines, street prostitutes, sex traffickers, call girls, mistresses.

The siren as a role serving the community was perfected by the stunning hetaira-–a creation of the Greek world. In Wolff's schema, the hetaira is that classical figure who illustrates personal and individual relationships which are not concerned with group identities--especially not with the family. Gradually my argument with this structural form as separate came from the need for each relational role to include the hetaira's expression of individual freedom within the context of the community's recognition of diversity contributions. Freedom supports creative problem solving for the common good. When creative freedom is not appreciated as critical to other social roles, the absence contributes to a social conservatism that values tradition and control over threatening innovation and which tolerates class distinctions. From this perspective,each social role benefits from the youthful desire which excites hope and imagination.

When the hetairan role is separately constructed, the community projects on individuals the need to perform and never grow old. Some movie actors, rock singers and artists—fantastically burdened by the demanding projections placed on them--suffer from these projections and find themselves ravaged by vorracious demands that they gratify the desire for youthful beauty and daring. Presented with idealized expressions of beauty, rebellion and independence, we fail to associate the creative strength of innovation and the occasional courage to be different with the other relational roles. We-make-dull. The community loses vigor and relevance, encourages destructive pornographic imaginations, produces stereotypical and infantile scripts as compensations for strictures inhibiting free expression.

My passion for reading from many traditions found primary sourcebooks in the South American women who came to the Chilean School, in the team which created the School, in the friend who translated and bridged my northern distance from the deep south. Grappling with the forces destroying their communities, these women searched for a spirituality to meet community needs. Among them I experienced the possibility of recasting Wolff's relational schema. We needed to pose a question: what energy force can challenge the destruction of the planetary home being engorged, plundered, stripped at an extraordinary rate? Are there creation myths in which otherness is honored as co-creator, in which the earth itself is understood to be a living being participating in the reproductive energy which is interactive and renewable? Which archetypal energies express the creative force of the universe?

Guided by many who have written thoughtfully on desire: Buddhists—especially scholar Anne Carolyn Klein writing on unbounded wholeness--, and European psychoanalysts and scientists like Julie Kristeva and David Bohm, I came to believe that Wolff's schema could be reset. A relational schema could infuse each of its aspects with the desire firing interaction. In childhood, in the final book of My Book House set, I was introduced to The Divine Comedy. Dante's Paradiso focuses on his final vision of the love that moves the sun and stars. Neither the constant birthing forth of the Mother Earth or the constant guidance of the Father Guardian sufficiently function as archetypal containers of the energy stream which Dante calls the love that moves the sun and the other stars. Here the archetypal idea of relationship and of creation-in-motion links creative power to the love which desires and directs awareness to love, to that force which accounts for a universe vast, ancient, ongoing.

Social propriety, tending to place an impossible social burden on stereotypical puer types, insinuates that they alone activate and sustain courageous and inventive explorations, confront rigid structures, foment rebellions. However, if the mother, amazon and medium as relational roles share responsibility for the hetairan desire for free agency and the opportunity to think futuristically and to take risks, there can be responses to both the unknown future and to present threats to sustainability. In wondering if the schema of four is better cast as a schema of three distinct competencies enriching the community, I am envisioning an integration of the hetaira as a force present within all forms and at the service of the community of life. The youth of the hetaira is a material symbol of the kinesthetic and visual and auditory sense of an impending future. A productive tension existing between honoring tradition and evolving and adapting evokes resistance to change until it becomes evident that change can be life giving. Integration of this energy assures that each form is serving the community's need for hope.

Joining with the South Americans in explorations of our spiritual lives led to our review of creation myths shaping Western spirituality and to finding in images of the sacred—both ancient and contemporary-- the experience of the natural world. Early artifacts from the cultures of the Euphrates and later artifacts from Neolithic nomadic peoples spoke to us of ancestral experience of the numinous. As a contemporary metaphor, nomadism characterizes postmodern life in placing critical value on the enormous vitality of the material world.

Vitality as a summary attribute tends to minimize the distinction between the natural world of the senses and the supernatural and invisible world of spiritualities and rituals. Vitality also characterizes an ethical approach to relationship, a metaphor for the ethics of the new materialisms. The realities of survival competencies necessary to the migratory life style of the Eurasian nomadic life challenge the deadening aspects of what might be termed the old materialisms--the repressive forces of overarching global and capitalist modalities. Cultural distances are evident between the crowded first world capital cities and the tent lives of Asian peoples, here represented electronically and expressed in traditional song, in the dress and instruments of the musicians, in the pride of heritage.

An exploration of evolving spiritualties continued to the School's conclusion. In this reflection I have recalled my childhood exposure to folk literature and its enthrallment with the natural world. These early experiences, seemingly forgotten, influenced my cross cultural experiences in South America recovering distant recollections of magical and spiritual forces in the natural world. This seeming regression allowed a new awareness of deep history, of evolution and of the significance of an emerging consciousness gained from perceptions of the living worlds of plants and animals.

The School immersed us in cosmological rituals, in the labyrinth of reflections, in perspectives describing our relationship to the material world and the origins of human life. We were attentive to regional stories of the divinities of deep history and the customs preserved in indigenous groups. Local tales of these societies and their migratory patterns included stories dealing with the denigration brought about by injustice, by slave labor, by caste systems. AIDS plagues suffered by children, theologians let go because they were not priests, women experiencing no protection from violence—these were the social realities the School's participants faced in their communities. Concurrently, the spiritual powers inherent in the material world included the human belief in a spiritual destiny and in the dream that the soul survives the death of the body. The source of sin and degradation in early Greek and Hebrew stories lay in the disobedience of women and in the consequent contamination of aspects of the natural world. In some contrast to this perspective, indigenous Sin Eater tales presented female divinities using the magic of their bodies to ingest and transform the contamination causing shame for the sinner.

According to Hesiod, historian of the earliest histories, the beautiful and deadly source of all human suffering was the first woman ever created: Pandora. By means of this denigrated image of the maternal figure birthing sin and sorrow, the first woman is that doorway through which evil enters the world. Pandora allows us to project on an alluring feminine figure. She represents a projection upon the natural world with its endless resources as needing to be controlled, altered, purified. Pandora and other late female divinities exemplify a hierarchical perspective on the natural world permitting and even requiring ownership and exploitation of resources. The Sin Eater goddesses, on the other hand, represent much earlier feminine deities whose power is directed toward transformation of human sinfulness via mercy and regeneration.

Liliana Kleiner, Lilith by the Red Sea

Sin Eater goddesses, in their ability to take on the sins of humans and transform them, confront despair and offer hope and an emergence from suffering into forgiveness. They epitomize an evolving spirit possessing both an ethical capacity to discriminate and a divine ability to have mercy. Some of these divinities possess both male and female characteristics representing miraculous co-creative reproductive capacities. Such images seem suited to share the contemporary consciousness of scientists exploring the mysterious universe of fractals, string theory, the search for the Higgs Boson.

Toni Wolff's schema of four ways of relating allowed the School of Ecofeminist Spirituality and Ethics to study the results of integration and growth from the perspective of diverse social experiences. It also allowed for examination of images of diversity and equality and the status given to women's innovative contributions to community. The schema's four distinct forms contained in one archetypal form, the Mother Earth, provided an opportunity to affirm difference contributing to relationship in community and led to closer examination of mythologies of origin beyond those of our own planetary explanations which allow a split between the material reality of Mother Earth and the dynamic possibilities of the Sky Father universes.

Over a ten year period the School explored four ways of relating as well as the implications of male mythologies having robbed the Christian iconography of the feminine. As we grew in understanding the universal appeal of the hetaira's youthful spirit, and especially as we recognized the expression of this relational form as necessary for innovation, we better understood the volatile nature of relatedness. From these experiences I began to grasp the significance of hetairan desire for autonomy as the energy necessary to each expression of relationship. Each relational role must allow for the youth, the girl within, to speak to the dream that is possible.

Friedensreich Hundertwasse